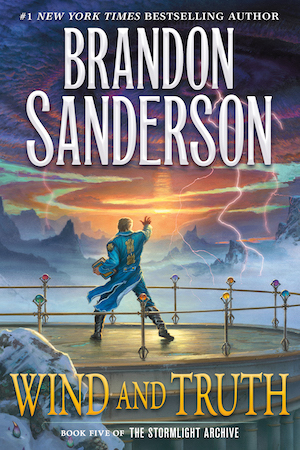

Brandon Sanderson’s epic Stormlight Archive fantasy series will continue with Wind and Truth, the concluding volume of the first major arc of this ten-book series. A defining pillar of Sanderson’s “Cosmere” fantasy book universe, this newest installment of The Stormlight Archive promises huge developments for the world of Roshar, the struggles of the Knights Radiant (and friends!), and for the Cosmere at large.

Reactor is serializing the new book from now until its release date on December 6, 2024. A new installment will go live every Monday at 11 AM ET, along with read-along commentary from Stormlight beta readers and Cosmere experts Lyndsey Luther, Drew McCaffrey, and Paige Vest. You can find every chapter and commentary post published so far in the Wind and Truth index.

We’re thrilled to also include chapters from the audiobook edition of Wind and Truth, read by Michael Kramer and Kate Reading. Click here to jump straight to the audio excerpt!

Note: Title art is not final and will be updated as soon as the final cover is revealed.

Chapter 23: Compromise

Would that men could always do the same—if I could enshrine one law in all further legal codes, it would be this. Let people leave if they wish.

—From The Way of Kings, fourth parable

The drizzle had fully committed to rain by the time Radiant’s team moved into position. If those last few Ghostbloods were coming to the meeting, they would arrive soon. And if there weren’t more coming… well, an enemy conference was likely underway, making it even more important that Radiant get into that hideout.

So, she helped Red wheel a small tool cart down the roadway, past rainspren like candles, each with a single eye on the top. They reached an intersection right in front of the Ghostblood hideout. She found the Ghostbloods setting up here to be impressively blatant. When others made hideouts in grimy corners of the worst parts of a city, they chose the middle of a storming military camp. Some people higher in the Alethi military must be in Mraize’s pocket. She’d have work to do uncovering them all.

Once in position, she and Red began to set up a small pavilion in the rain. They’d dropped their Lightweavings, relying on hooded cloaks to mask their faces, in case that sand could reveal them. Soon someone from the Ghostbloods—as expected—came to check on them.

It wasn’t the masked guard. Damnation. Radiant kept calm and allowed Red to handle it while she hung back, fiddling with their tools. The guard she wanted—the one with the mask—emerged from the shadowed porch but did not approach.

“Hey,” the other Ghostblood said as he arrived. “What’s this?” His name was Shade, a man with Horneater blood, though he looked more Alethi despite the forked beard. She thought the masked woman had fetched him as they were setting up.

“We’re supposed to level this intersection,” Red said. He noted Shade’s Alethi uniform. “I have the orders somewhere, Sergeant.”

“You’re supposed to work in the rain?” Shade demanded.

“Yeah. Storming unfair.” Red thumbed at the little pavilion. “At least we’ve got that. If you want to take it up with the camp operations commander, I wouldn’t mind a little time off.”

Shade picked through the tools, then poked around in the pavilion—while the masked guard lurked by the building. Adolin’s sessions with Radiant let her spot the readiness of a trained soldier: the stance, the alert attention.

Calm, careful, Radiant rearranged the tools after Shade finished poking through them. He was built like a boulder, so it would be easy to assume he was the more dangerous, but he didn’t have the casual grace the masked woman did. Shade stepped back in thought, rain dripping down his beard. He wouldn’t want to draw attention, but he also wouldn’t want random workers so close to their base, maybe hearing things they shouldn’t.

“Pack up and work somewhere else,” he told Red. “For at least a couple more hours. You don’t need authorization; just tell them I gave the orders.”

Red glanced at Radiant, and—hood pulled tight—she nodded.

“Yes, Sergeant,” Red said with a sigh.

The two of them slowly began disassembling the pavilion. Shade returned to the masked guard and they exchanged whispers. Then the guard fell into position by the door while Shade slipped inside, passing a large jar of the black sand that had been tied hanging outside.

“That’s a problem,” Red whispered over the sound of beating rain. “Did you catch their exchange?”

“Mmm…” Pattern said from Radiant’s coat. “He said, ‘I want them gone by the time Aika and Jezinor get here.’ And the woman said, ‘Ya.’ ”

“We were supposed to lure out the short one,” Red said. “We need that mask.”

“I’ll go in close and deal with her,” Radiant said.

“You sure?” Red asked. “What if she makes noise?”

“I’ll be quick,” she replied, noting Gaz as he came trotting up to them.

“My part’s done,” Gaz said. “Why are we taking the pavilion down?”

“Get angry about it,” Radiant said, with a nudge from Veil. “Demand to know who gave these orders. Pretend you’re our foreman.”

Gaz launched into it with gusto, complaining loudly that they didn’t have authorization to set up anywhere else. He did well enough he even drew a few angerspren. Perfect. Shallan and Red set up the pavilion again—they’d barely started disassembling it—while Gaz demanded to speak to the sergeant who had changed their orders. With that as an excuse, Radiant told Pattern to wait behind, then walked over to the building. She stepped out of the rain into the covered porch, and hesitated by the door.

The guard emerged from the shadows, mask peeking from the front of her hood. As on Iyatil, it made the woman seem… inhuman. Painted wood, without carvings of facial features—hiding all except those eyes. Locked on to her.

“Oh!” Radiant said. “Sorry. But, um, our foreman wants to talk to you. Um. It’s… um. Sorry…”

The guard took her by the arm. Radiant twisted and whipped up her other hand—pushing a small stiletto toward the guard’s throat. The enemy caught it, her eyes narrowing, then grunted and shoved Radiant backward, trying to trip her.

A year training with Adolin gave Radiant some unexpected grit. She resisted the shove and kept her stance, locking eyes with the masked creature.

Now, she ordered her armor.

In a blink, the armor formed. Not around her, but around the guard, freezing her in place as it had Red earlier. Radiant caught a glimpse of a pair of shocked eyes as the helmet encased the woman’s face.

Shallan! the creationspren said, eager.

“Just keep her mouth closed,” she said. “Like the drawing Shallan did for you. Right?”

Shallan! they replied in a chorus. The only sound from the guard was muffled exertion, so hopefully the helmet plan was working. Radiant thought they’d explained it well enough to the creationspren: a mechanism that held the jaw shut by making the helmet tighter at the bottom, below the mask.

She checked the sand in the hanging jar. Still black, as she’d hoped. They’d said that it took an intelligent spren to activate the stuff—which made sense, otherwise it would be useless, turning white in warning whenever someone got anxious. Her Plate spren hadn’t affected it even when forming.

Red and Gaz came jogging up. “It worked,” Radiant whispered, her heart thumping from the exchange.

Gaz nodded toward the woman’s motionless left hand, raising a knife toward Radiant—the gauntlet had simply formed around it, letting the blade peek out. She’d missed that entirely. A good warning. A year of practice had given her some skill, but it was a weak substitute for a lifetime of battle experience.

“Eh,” Red whispered, wheeling over the cart, “she could have healed from it.”

“And what would that have done to the sand?” Gaz whispered, gesturing toward the glass jar. “We’re not sure if a healing will activate it or not. If so, the first person who stepped through that door would have known a Radiant had been here.” He inspected the armor closer, locked down as it was. “Yet this did work. I can barely hear her.”

The captive woman didn’t even tremble from struggling to escape. Together, they managed to tip her into the two-wheeled cart, throw a tarp over her, then wheel it into their small pavilion. Had any guards on the walls seen? Darcira and the strike team were poised to intercept any who came running, but still she worried.

Move quickly, Shallan thought, taking over from Radiant. She didn’t want the last few Ghostbloods to arrive at the door and find the guard missing.

Gaz put his arms around the head of the armored woman to be in position. He nodded.

Shallan touched the armor. Could you dismiss just the helmet please? she asked.

Shallan! the armor said. The helmet vanished in a puff of Stormlight. Gaz snapped his arms around the woman’s neck, executing a perfect choke hold. Shallan needed Radiant again for a moment while watching the struggling woman be strangled, her eyes bulging, her skin going a deep red around the mask.

Gaz didn’t kill her, though he held on longer than Radiant thought necessary. He’d explained earlier: assuming your attacker didn’t want to kill you, the best way to escape a choke hold was to pretend to fall unconscious early. So Gaz ignored the struggles, the painspren, the frantic eyes, the sudden limpness and counted to himself softly.

She’d never asked how he knew this so well.

Gaz nodded, and Shallan dismissed the armor, then began stripping to her undergarments while the two other Lightweavers efficiently undressed the guard, then bound and gagged her. Gaz had warned Shallan that people usually didn’t stay unconscious for long after being choked out. Indeed, the guard was stirring as Shallan finished re-dressing, wearing the woman’s clothing. Utilitarian brown leathers that weren’t particularly formfitting, along with a hooded cloak and a frightening number of knives strapped across her person.

Though Shallan was accustomed to being short compared to the Alethi, she was a tad taller than this offworlder. Close enough, hopefully. She already had her hair under a wig, but her options had been limited, so she was distressed to notice that the guard had closer-cropped hair than the pictures had depicted. Storms. She’d cut her hair, which meant Shallan would have to leave the hood up indoors. Would that seem odd?

Red knelt beside the figure, then—appearing more unnerved by this than stripping a captive—tried to figure out how to remove the mask. Turned out it was bound in place by two cords, which he undid, and pulled the red-orange mask free. Shallan had expected it to stick—she’d always felt that Iyatil had worn hers so long that the skin had grown over it. That proved an incorrect assumption; the mask was obviously removed and cleaned often, but it was also worn so continuously that it left imprints on the guard’s face.

Her skin was as pale as Shallan’s, and without the mask she seemed far less dangerous. Though she was probably in her middle years, her face was smooth, almost childlike.

Stop that, Shallan thought, taking the mask from Red. You need to stop comparing all Shin people to children. It was a bad habit. Besides, this woman wasn’t even Shin—she was an offworlder who just happened to look Shin.

Shallan tied on the mask and pulled up her hood. The mask covered her full face, and was peaked slightly at the center, sloped at the sides. It was wide enough that her ears would barely be visible. Aside from the eyeholes, it had two holes near the nose for breathing, and a small portion was missing for the mouth—like a bite had been taken out of it at the chin.

Red nodded. “Looks pretty good.”

“I don’t know,” Gaz replied, scratching his cheek. “It would fool a casual passerby. But Ghostbloods?”

Shallan fell into an imitation of the woman’s stance. Dangerous, ready. Stepping with the kind of casual grace that took years to perfect. She narrowed her eyes behind the mask, mimicking the woman’s expression—conveying it through posture.

Well done, Veil thought.

Red glanced at Gaz, cocking an eyebrow.

“All right, fine,” Gaz said. “I still find it creepy how she can do things like that. Just don’t take the hood off. The hair is wrong.”

A moment later, Darcira ducked into the pavilion. “You’re not in place yet?”

“Going now,” Shallan said in a whisper, as it was easier to mask her voice that way.

“Did you find your watchpost?” Darcira said to Gaz.

“Yeah,” he said. “Neutralized them fast enough to show up here and help. What took you so long?”

“Had to go and position the strike team, if you forgot,” Darcira said. “What do we do if there were more than two observation posts watching the base?”

None of them could answer that, but they’d spotted only two in their sweep of the area. They had to trust in their skills. Shallan slipped one of her team’s spanreeds into her sleeve, glanced at Pattern—dimpling the wood of the cart, humming to himself nervously—then waved goodbye. She left them, instead falling into place by the alcove. She maintained the same posture and stance as before. Sticking to shadows. Not speaking.

You can do this, Veil whispered.

Her heart still thrummed like listener war drums. She was going to enter the enemy stronghold alone—and could not use her powers. But it was the only way. What did you do when there was a guard watching for you?

You became the guard.

Not five minutes later, Shallan spotted two people trotting up to the safehouse. Aika and Jezinor, a pair of Thaylen traders. They’d arrived with Queen Fen’s retinue, which explained why they were some of the last. They’d needed to find an excuse to come to the Shattered Plains.

Shallan’s nervousness faded as she made a good show of checking their features with her hands, then holding the glass jar of sand up to each one. Neither seemed to notice anything off. She knocked on the door, as she’d seen done before. Shade opened it and waved the other two in. Shallan slipped in herself, and he held the door open for her. They’d be trusting their watchposts to send spanreed warnings if anything approached the safehouse. Posting a guard outside for too long risked drawing attention.

This was it. Veil was right, she could do this. Unless they asked her to say too much. Unless there was a third watchpost they hadn’t found. Unless her disguise failed.

It was too late now. She had walked confidently straight into the den. Now she either proved to be a predator herself, or she got eaten.

* * *

Navani left Dalinar alone in the room with the plants to talk to the Stormfather while she stepped outside with the others, knowing he’d fill her in later.

She entered a world of chaos. Strategists planning, messengers running orders, a world spinning up to deal with another crisis. It was time to be a queen. Which regrettably meant dealing with all the random issues that no one else could. At the perimeter of the room, at least a dozen people waited for her attention.

So many systems had fallen apart during the occupation. Schooling had been ignored. Trade for less important supplies—everything from extra buttons to feed for pet axehounds—had been interrupted. Now, with the tower awakened, many problems were being solved while others—such as who got to use which services when—were just beginning.

They could handle it without her, but they didn’t know it. And… perhaps she needed to banish such thoughts. She was important to the administration of this tower, this kingdom. Vital even.

So she went into motion, assigning some of her staff to various problems. Makal to rehouse people whose living quarters now turned out to be important for other reasons. Venan to organize meals for everyone attending the meeting, and to covertly keep a list of who was sending what messages where, just in case.

Next she found Highprince Sebarial and Palona waiting for her. They had learned an unfortunate lesson: that sometimes you had to put yourself where Navani could see you in order to get her time. They had questions about how to get supplies into the city if there was a war on the Shattered Plains.

“We can’t keep relying on the Oathgates,” Sebarial said, rubbing his forehead. The girthy man had gone back to wearing an open-fronted takama, now that the weather was summer at the tower, and his belly poked out in a way he reportedly thought was distinguished. “But organizing shipments from Azir up through these mountains is going to be an enormous hassle. Flying them in will be prohibitively expensive in Stormlight unless we can make more airships. Yes, we can grow food now, but other supplies…”

“Bring me proposals,” Navani said, looking over Palona’s ledgers.

“This was supposed to make me rich!” Sebarial said. “I was Highprince of Commerce! I was supposed to be able to skim thousands to line my own pockets! But I can barely make any of this balance. There’s nothing to skim!”

“Don’t mind him, Brightness,” Palona said. “He’s having a rough time with how responsible he’s becoming.”

“You’re good at being useful, Sebarial,” Navani said. “That’s the problem, isn’t it?”

“My darkest secret,” he grumbled. “I still pay for my household staff, vacations, and massages out of public funds, I’ll have you know. It’s a huge scandal.”

“I’m sure Brightness Navani knows what a miscreant you are, gemheart,” Palona said, patting his arm.

He sighed. “We’re mobilizing troops to Thaylenah and the Shattered Plains. You’re authorizing active battle pay, then? You realize this is going to dip into what little we have remaining? We might be able to offer extra rations instead of battle pay in some cases.”

“Thank the Almighty for the emeralds we got on the Shattered Plains,” Palona said. “It’s the only way we’re making enough food for everyone right now.”

“I’ll see if we can get more time with the Radiant Soulcasters,” Navani said. “Given the way the tower is functioning, we can have them working at an increased speed.”

“They break gemstones as they work, Brightness,” Sebarial said. “Even Radiant Soulcasters need gems as a focus, which means we can’t continue like this forever. We’ll need a gemheart ranch up here, but there isn’t a lot of space, so we can’t lose the Shattered Plains.”

She did her best to calm him, then took a meeting with Highprince Aladar on the status of the lighteyes. There was a lot of general panic about Jasnah’s work to free the Alethi slaves, a decision that Dalinar had copied for Urithiru after some persuasion. It would be a slow process, designed to take effect over time, with social systems in place to facilitate. Jasnah, as usual, had done her research.

However, the lighteyes were pushing back. “Tradition will be cast to the winds,” Aladar said. “The upright, natural order of things is being trampled. How can the lighteyed families maintain themselves without lands and taxes? What does it even mean to be lighteyed any longer?”

“It means what it has always meant,” Navani said.

“Which is?” Aladar asked. “Brightness, with the elevation of Stormblessed to a full house, and now to third dahn, what about the other Radiants? More than three-quarters of them were darkeyed and are now light. It’s chaos!”

“It’s a problem for after the contest, Aladar,” Navani said. “When we’re not focused on a mass invasion. For now, I need logistical work from you. Make certain that supplies are transferred per the generals’ requests. Fen can provision some of the soldiers we send her, but if we move battalions to Narak they’ll run out of water quickly if we don’t prepare. Also, make sure to check on Adolin and get him what he needs.”

The stately bald man shook his head and sighed. “As you wish—but my concerns won’t go away, Brightness. This problem is a bubbling cauldron. It’s going to overflow. Only the invasions are stopping it.”

“I know,” she said. “But let’s worry about the crisis we are facing now first, Aladar.”

He bowed, then went to see to her orders. She tried not to be annoyed—and commanded the appearing irritationspren to vanish. Aladar was reasonable for a highlord, and was simply passing on what the less reasonable highlords were thinking. They were a powerful contingent, and hadn’t failed to notice that—after years of politicking—almost everyone who had opposed Dalinar was now dead. Rumors about what had really happened to Sadeas churned, for all that Jasnah worked behind the scenes to quash them.

Yes, the upper ranks of the lighteyes were a bubbling cauldron. Unfortunately for them, the darkeyes had been boiling for far longer—and they suddenly had access to advocates in the form of people who could bend the laws of reality. She suspected that if it came to a head, the lighteyes would discover how little “tradition” was worth in the face of centuries of pent-up rage.

Navani put that problem out of her mind for the time being. It was dangerous to do so, but she had to perform mental triage. War was upon them, and for eight more days she needed to keep everyone pointed the same direction. She worked through a dozen other problems as functionaries and aides found her. She kept turning and finding lifespren swirling around her, or gloryspren skulking by the ceiling, or any number of them darting around. It was like she was some storming heroine from a story, the silly type where a young and innocent girl always had a thousand lifespren or whatever bobbing around her.

As she worked, she kept glancing toward the room where Dalinar met with the Stormfather. He’d always been ambitious. But this?

Is it right, what he contemplates? she asked the Sibling. Ascending to Honor?

Someone will need to eventually, the Sibling said. The power can’t be left to its own devices. It will come awake.

Why hasn’t it already? It’s been thousands of years.

Whatever the reason, be glad. These powers aren’t like the tiny pieces that become spren. The power of a Shard needs a partner, a Vessel. Without it…

What? Navani asked.

Great danger. We do not think as humans do. To separate the power from those who are attached to the Physical Realm… that should frighten you. It is not so terrible a thing for part of me to despise you. But for the power of a god to? Dangerous. For all of us.

Navani shivered at the Sibling’s tone, but had to keep working. She checked in with her scholars, who had been waiting patiently in the next room—one of the few small ones that made a ring around the lifts up here. Inside, seven ardents had set up a display. Navani hated to make them cart it all the way up here, but despite the faster lifts, there just wasn’t time for her to go elsewhere for meetings. People needed to come to her.

Rushu met her at the doorway, in her usual grey ardent’s robes, sweat trickling down her brow. Indeed, this room was uncomfortably warm. The pretty woman was, as usual, trailed by several young male ardents eager for her attention. In this case they’d volunteered to set up Rushu’s presentation. Even after all these years, Navani couldn’t decide if Rushu was oblivious or deliberate in the way she ignored masculine interest.

“Brightness!” Rushu said, bowing as she entered. “Thank you for making the time.”

“I don’t have long, I’m afraid,” Navani said. “Dalinar’s antagonizing the Stormfather again, and I’ll need to go the moment he’s ready to talk.”

“Understood, Brightness,” Rushu said, walking her to a counter set up with some fabrials and a small oven burning Soulcast coal, of all things. A separate attractor fabrial above it collected the smoke and invisible deadly gases in a sphere of swirling blackness, allowing the small oven to burn without scent or the need for a chimney. Flamespren played within, their iridescent forms mimicking the shape of the fire and the molten red coloring of the hearts of coal.

Beside the oven was a more modern heating device, a large ruby fabrial like the ones they’d installed in many rooms. Those were proving, to the Sibling’s annoyance, more effective than the tower’s ancient methods, which required heating air in a boiler at the center of each floor, then blowing it into the specific room when requested. While that was amazing, a simple ruby heating fabrial didn’t waste energy keeping massive boilers going all the time. Unfortunately, modern fabrials had other problems, at least in the eyes of the Sibling.

“We’ve only had a day or so to work,” Rushu said, “but I wanted to show you our progress. This was an enlightened idea you had—and could revolutionize the fabrial art! Brightness… this could be your legacy.”

“Our legacy, Rushu,” Navani said. “You’re doing the work.”

“Pardon, Brightness. It’s your idea. Your genius.”

Navani prepared another complaint, then… then discarded it. Storms, maybe she was growing. “Thank you, Rushu. Let’s not assume we’ve changed the world after one day’s work though. Show me what you’ve done.”

Rushu unlatched the glass front of the oven. The group of flamespren within shivered as the cool air entered, then continued to frolic, taking the shapes of small minks cavorting over the surface of the burning coal.

She plucked a coal out with a pair of tongs, then nodded to one of her assistants. The heating fabrial next to the oven had an outlet valve: basically, a hole drilled into the gemstone that they kept plugged with an aluminum stopper. The assistant unscrewed the plug and opened the valve, usually something quite inadvisable. Because the moment he did so, the flamespren in the heating fabrial—a vital piece of what powered it—would escape.

This one scrambled out onto the plug and immediately started to vanish back into the Cognitive Realm. Then Rushu held her coal close to it. Another ardent used tuning forks to play what they hoped was a comforting tone to the spren. Instead of vanishing, the flamespren hopped onto the coal in Rushu’s hand and let her deposit it in the oven. She came out a moment later with a different flamespren on another coal, blinking glowing red eyes, red “fur” blazing along its form.

Calmed by the tone, it let her bring it over to the fabrial. They trapped it inside using modern techniques of Stormlight diffusion. Then, with the gemstone plugged and a new spren inside, they recharged the fabrial with a Radiant’s help and turned it back on so it began heating again.

What abomination are you creating now? the Sibling asked in Navani’s head.

Abomination? Navani replied. Did you not see what we just did?

Enslaving spren, the Sibling said, in torment and captivity.

Navani leaned down by the front glass of the oven, where the spren were scampering across the coals. Torment, you say? Tell me, Sibling, which of these spren was the one held captive? If it was tormented, I can’t see any lasting effect.

It’s still wrong to keep spren in such small prisons, the Sibling said.

“Brightness,” Rushu said, leaning in beside her and looking at the spren in the oven, “this is really possible. Did you read the writings of Geranid and Ashir I gave you?”

“Some of it,” Navani said. “Before the invasion. I know they’ve been able to keep the same flamespren for months at a time, without losing them to the Cognitive Realm. It requires maintenance of a fire.”

“Yes, but there’s more!” Rushu said. “Their research taught me something amazing: the flamespren will stay even longer if you give them treats.”

“What kind of treats do flamespren want?” Navani asked. “More coal?”

“Names,” Rushu said. “Names and compliments. Brightness, if you think about the spren, they mold to your thoughts.”

“I read about the molding process,” Navani said. “If you measure them, they lock to those measurements. But… compliments?”

“This one is Bippy,” Rushu said, pointing to one of the spren. “See how its head has that little tuft on top?”

Bippy looked toward them at the attention, then hopped up to the edge of the oven, staring out with too-large eyes. A bit of fire itself, responding to Rushu merely mentioning its name.

“Fascinating,” Navani said as some of the gloryspren that trailed her began to spin around the two of them.

“We can cultivate them over time,” Rushu said. “An entire… herd? Pod?”

“I’m voting for a flare,” one of the other ardents said. “A flare of flamespren.”

“An entire flare, then,” Rushu said, “of domesticated flamespren. It’s too early to tell, but Brightness, you might be right. If they can be trained… then we can teach them to go in and out of fabrials on command.”

Domesticated flamespren? the Sibling asked. Nonsense.

Is it? Navani asked, still watching Bippy. Rushu moved her finger back and forth in front of the glass, and Bippy ran to follow it. When Rushu complimented the spren on its trick, Navani could have sworn that Bippy glowed brighter. Intelligent spren seek bonds with people. Why not lesser spren?

It… it isn’t natural, the Sibling said.

Pardon, Sibling, Navani said. But neither is living in towers that are climate controlled. If we conformed only to what was natural, my people would be living naked in the wilderness and defecating on the ground.

The Sibling simmered in the back of her mind, like a burning coal themself.

You’ve said our practices are cruel, Navani said, trying to soften her tone. I’m attempting to do something about that. We keep chulls as beasts of burden; can we not do the same for spren? If being in a fabrial is uncomfortable for a spren… well, so is pulling a cart for a chull. But assuming it’s not too bad, we should be able to train them to do it willingly, with rewards. We can … cultivate them, Sibling. Isn’t this a better way? To have spren take shifts in the fabrials, with training to get in and out willingly?

She held her breath, waiting. The Sibling had been hard-nosed about this.

See my heart, Sibling, she sent. See that I’m trying.

I see, the Sibling said. Rushu jolted and looked around, as did the other ardents, indicating the Sibling had chosen to be audible to them as well. This is a good thing you attempt. All spren being free would be preferable. But… if this works… perhaps I can see a compromise. Thank you. For listening and changing. I had forgotten that people are capable of that.

Navani released a held breath, and with it a mountain of tension. Rushu’s eyes had gone wide, and the ardent fiddled in her pocket, pulling free a notebook.

“Sibling?” Rushu whispered, awespren bursting around her. “Thank you for talking to me. Thank you so much!”

What is this? the Sibling asked Navani.

Rushu’s been asking after you constantly since we bonded, Navani thought. Haven’t you heard?

As I said, I don’t pay attention to every word spoken inside my halls, the Sibling said. Only to what is relevant. Then, after a pause, they continued, Is this relevant?

To Rushu, yes, Navani said.

With her notepad out, Rushu bit her lip and looked to Navani pleadingly.

“Rushu would like the chance to talk to you,” Navani said out loud. “I think she wants to ask you about fabrials.”

“Very well,” the Sibling said, and Rushu gasped softly. “You should go, Navani. I believe your husband’s conversation with my sibling is finished. There will be ramifications.”

Navani nodded. As she left, though, she heard the first of Rushu’s questions—and was surprised that it wasn’t about fabrials at all.

“Navani tells me,” Rushu said, “that you are neither male nor female.”

“It is true.”

“Could you tell me more about that?” Rushu asked.

“To a human, it must sound very strange.”

“Actually, it doesn’t,” Rushu said quietly. “Not in the slightest. But talk, please. I want to know how it feels to be you.”

Navani left them to it, pleased. The fabrial experiment showed promise—but more, if she could get the Sibling talking to other scholars, she suspected that would help with the spren’s reintegration. So far, the Sibling only worked with them because Navani had essentially bullied them back into a bond. The more friends, or at least acquaintances, that the Sibling had, the better.

For now though, it was time for Navani to deal with another spren. And with a husband who had decided to become a god.

Chapter 24: In the Dancing Ring

Twenty-six years ago

Szeth-son-Neturo found magic upon the wind, and so he danced with it.

Strict, methodic motions at first, as per the moves he had memorized. He stepped and spun, dancing in a wide circle around the large boulder. Szeth was as the limbs of the oak, rigid but ready. When those shivered in the wind, Szeth thought he could hear their souls seeking to escape, to shed bark like shells and emerge with new skin, pained by the cool air—yet aflush with joy. Painful and delightful, like all new things.

Szeth’s bare feet scraped across the packed earth as he danced, getting it on his toes, loving the feel of the soil. He went right to the edge, feet kissing the grass—then danced back, spinning to the accompaniment of his sister’s flute. The music was his dance partner, wind made animate through sound. The flute was the voice of air itself.

Time became thick when he danced. Molasses minutes and syrup seconds. Yet the wind wove among them, visiting each moment, lingering, then dashing away. He followed it. Emulated it. Became it.

More and more fluid he became as he circled the stone. No more rigidity, no more preplanned steps. Sweat flying from his brow to seek the sky, he was the air. Churning, spinning, violent. Around and around, his dance worship for the rock at the center of the bare ground. Five feet across and three feet high—at least the part that emerged from the soil—it was the largest in the region.

When he was wind, he felt he could touch that sacred stone, which had never known the hands of man. He imagined how it would feel. The stone of his family. The stone of his past. The stone to whom he gave his dance. He stopped finally, panting. His sister’s music cut off, leaving his only applause the bleating of the sheep. Molli the ewe had wandered onto the circular dance track again, and—bless her—was trying to eat the sacred rock. She never had been the smartest of the flock.

Szeth breathed deeply, sweat streaming from his face, wetting the packed earth below with speckles like stars.

“You practice too hard,” his sister—Elid-daughter-Zeenid—said. “Seriously, Szeth. Can’t you ever relax?”

She stood up from the grass and stretched. Elid was fourteen, three years older than he was. Like him, she was on the shorter side—though she was squat where he was spindly. Trunk and branch, Dolk-son-Dolk called them. Which was appropriate, even if both Dolks were idiots.

She wore orange as her splash: the vivid piece of colorful clothing that marked them as people who added. One article per person, of whatever color they desired. In her case, a bright orange apron across a grey dress and vibrant white undergown. She spun her flute in her fingers, uncaring that she had broken her previous one doing exactly that.

Szeth bowed his head and went to get some water from the clay trough. Their homestead was nearby: a sturdy building constructed of boards, held together with wooden pegs. No metal, of course. Szeth’s father worked on the rooftop, plugging a hole. Normally he oversaw the other shepherds, visiting them to give them help. There was some kind of training involved, which Szeth didn’t understand. What kind of training did shepherds need? You just had to listen to the sheep, and follow them, and keep them safe.

Neturo was between assignments, working on the house he and his brothers had built. In a field opposite the home—distant but visible—the majority of their sheep grazed. A few, like Molli, preferred to stay close. Szeth liked when they could use fields near the homestead, as he could be near the stone and dance for it.

He dipped a wooden spoon into the trough and sipped rainwater, pure and clean. He peered through it to the clay bottom—he loved seeing things that couldn’t be seen, like air and water.

“Why do you practice so hard?” Elid said. “There’s nobody here but a couple of the sheep.”

“Molli likes my dancing,” Szeth said softly.

“Molli is blind,” Elid said. “She’s licking the dirt.”

“Molli likes to try new experiences,” he said, smiling and looking toward the old ewe.

“Whatever,” Elid said, flopping back on the grass to stare at the sky. “Wish there was more to do out here.”

“Dancing is something to do,” he said. “The flute is something to do. We must learn to add so that—”

She threw a dirt clod at him. He dodged easily, his feet light on the ground. He might be only eleven, but some in the village whispered he was the best dancer among them. He didn’t care about being the best. He only cared about doing it right. If he did it wrong, then he had to practice more.

Elid didn’t think that way. It bothered him how apathetic she had become about practicing as she grew older. She seemed like a different person these days.

Szeth tied his splash back on—a red handkerchief he wore around his neck—and did a quick count of the sheep.

Elid continued to stare at the sky. “Do you believe the stories they tell,” she eventually said, “of the lands on the other side of the mountains?”

“The lands of the stonewalkers? Why wouldn’t I?”

“They just sound so outlandish.”

“Elid, listen to yourself. Of course stories of outlanders sound outlandish.”

“Lands where everyone walks on stones though? What do they do? Hop from stone to stone, avoiding the soil?”

Szeth glanced at their family stone. It peeked up from the earth like a spren’s eyeball, staring unblinking at the sky, a vibrant red-orange. A splash for Roshar.

“I think,” he said to Elid, “that there must be a lot more rock out there. I think it’s hard to walk without stepping on stone. That’s why they get desensitized.”

“Where do the plants grow, then?” she asked. “Everyone always talks about how the outside is full of dangerous plants that eat people. There must be soil.”

True. Maybe the terrible vines he’d heard of stretched out long, like the tentacles you might find on a shamble, or one of the beasts that lived in the tidal pools a short distance down the coast.

“I heard,” Elid said, “that people constantly kill each other out there. That nobody adds, they only subtract.”

“Who makes the food then?” he said.

“They must eat each other. Or maybe they’re always starving? You know how the men on the ships are…”

He nervously looked toward the ocean—though it could be seen only on the sunniest days. Technically, his family was part of the farming town of Clearmount, which was at the very edge of a broad plain, excellent for grazing. This part of Shinovar wasn’t crowded; it was a day or two between towns. He heard that in the north there were towns everywhere.

The grassland bordered on the southeastern coast of Shinovar. Clearmount, and Szeth’s family homestead, was in an honored location near the monastery of the Stonewards, which was up along the mountain ridge. In Szeth’s estimation, this was the perfect place to live. You could see the mountains yet also visit the ocean. You could walk for days across the vibrant green prairie, never seeing another person. During the early months of the year they grazed the animals here, near their homestead. In the mid months they would take the sheep up the slopes, seeking the untouched and overgrown grass there.

He bent down next to old Molli, scratching at her ears as she rubbed her head against him. She might lick rocks and eat dirt, but she was always good for a hug. He loved her warmth, the scratchy wool on his cheek, the way she kept him company when the others wandered.

She bleated softly when he finished hugging her. Szeth wiped the salty, dried sweat from his head. Maybe he shouldn’t practice dancing so hard, but he knew he’d made a few missteps. Their father said that they were blessed as people who could add beneath the Farmer’s eyes. The perfect station. Not required to toil in the field, not forced to kill and subtract—allowed to tend the sheep and develop their talents.

Free time was the greatest blessing in the world. Maybe that was why the men of the oceans sought to kill them and steal their sheep. It must make them angry to see such a perfect place as this. Those terrible men, like any petulant child, destroyed what they could not have.

“Do you think,” Elid whispered, “that the servants of the monasteries will ever come out and fight for us? Use the swords during one of the raids?”

“Elid!” he said, standing. “The shamans would never subtract.”

“Mother says they practice with the Blades. I’d like to see that, hold one. Why practice, except to—”

“They will fight the Voidbringers when they arrive,” Szeth snapped. “That is the reason.” He glanced toward the ocean. “Don’t speak of the swords. If the outsiders realized the treasures of the monasteries…”

“Ha,” she said. “I’d like to see them try to raid a monastery. I saw an Honorbearer once. She could fly. She—”

“Don’t speak of it,” he said. “Not in the open.”

Elid rolled her eyes at him, still lying on the grass. What had she done with her flute? If Father had to make yet another… She hated when he brought that up, so he forced himself to stay quiet. He pulled away from Molli, and then looked down at the ground she’d been licking.

To find another rock.

Szeth recoiled, part shocked, part terrified. It was small, only a handspan wide. It peeked up from the earth, perhaps revealed by last night’s rain. Szeth put his fingers to his lips, backing away. Had he stepped on it while dancing? It was in the packed earth of the dancing ring.

What… what should he do? This was the first stone he’d ever seen emerge. The ones in other villages and fields—carefully marked off and properly revered—had been there for years.

“What’s up with you?” Elid said.

He simply gestured. She, perhaps sensing his level of concern, rose and walked over. As soon as she saw it, she gasped.

They shared a glance. “I’ll get Father,” Szeth said, and started running.

Excerpted from Wind and Truth, copyright © 2024 Dragonsteel Entertainment.

Join the Read-Along Discussion Here

Read the Next Chapter Here

Buy the Book

Wind and Truth